Connecting the present and the past: an interview with composer and pianist Alexander J. Schwarzkopf

This past year has taught us that for all that's been said about our joint journey through this pandemic, words frequently fail to express the depth of what we've endured. The shock, the fear, the whiplashing emotions--all of these things have been a kaleidoscope of reactions we've all experienced and continue to sort through. For many of us, there's no clear narrative, just the string of events and emotions that have formed this year.

This is why Alexander Schwarzkopf's latest collection of piano pieces, 27 Pandemic Preludes, is so powerful. Each short piece is a vignette, a jewel-box composition that highlights a moment in time or a snapshot of an emotion or experience. Alexander will premier these preludes on his YouTube channel on Sunday, March 14, 2021 at 1:59 pm PST, showcasing not only this beautiful collection of pieces, but also 18 Variations and a Coda on the Theme Frère Jacques, which he composed in 2019.

I've known Alexander for years and been an admirer of both his piano performances and his compositions for the ways he's guided by fierce intelligence and a dedication to exploring the limits of his ideas. From the pieces he's written for solo piano, to Psi, a piano concerto he was commissioned to write for the Oregon Music Teacher's Association, Alexander's music explores stretches the ear and the mind. It is an honor to feature him on No Dead Guys.

What drew you to music, and what inspired you to become a composer?

I played fiddle contests with my dad and older brother, 2nd violin in the Colorado Springs Youth Symphony as well as early Bach pieces before switching entirely to piano. I liked being able to see the keyboard layout. Music made more sense that way. Once I found the piano I never looked back. Becoming a composer is a question of whether or not you have something to say, it requires so much more than just learning notes. You have to think about the sound, develop a deeper relationship with rhythm and harmony. A composer must grapple with how to organize sound in time, which is much different than learning to count. My development in that direction was guided in part by my ear, my dad discovered I had perfect pitch when I was around 3 years old. Composers work diligently to develop what is call inner-hearing, or hearing the sound without an instrument. This is one of the primary means to discovering the right timbre and instrument to articulate the musical idea in your mind. I was particular about how I wanted music to sound when I played, which lead me to play many pieces “my way.” I would play pieces by Bach and Mozart upside down or backward. Later I grew to understand stylistic interpretation, worked tirelessly to develop my technique while never losing sight of that notion of how I wanted to the music to sound. I wrote a piano rag for a composition contest around age 12. That experience left me with a feeling of true accomplishment.

Youʼve created a career as a pianist, an instructor, and a composer. Why did you choose to pursue all three, and how do you find the time to maintain it all?

I find all aspects of the discipline to be rewarding and feel fortunate to practice the three that are most important to me. To me, the work of an artist is the process of developing your craft: practice, rehearse, perform, collaborate, write, teach, lecture, create...all of it is incredibly meaningful and important to me. During parts of my education, particularly the DMA, I did not compose much, aside from a few cadenzas for Beethoven and Mozart concerti and some unfinished opera paraphrases. I focused on performance of repertoire from the standard canon of piano literature and developed my teaching technique. I did, however, premiere my piano pieces “Dialogues” (2008) on my first DMA recital together with my “Kaleidoscopes” (2006, rev. 2007). To do it all is a dream, but requires you to do less of each. At times it is a little overwhelming, but in the end, it is about the process to me.

Your compositions include works for solo piano, piano concerto, piano duo, chamber music for cello and piano, violin and piano, slam poet and piano, piano trio, Augmented Reality and electronic media, songs for original theatre productions and choreography/composition for piano and dance. What instrument do you feel most perfectly expresses your creative voice?

Currently I compose primarily for piano. I wrote a piano concerto as my 2017 OMTA Composer of the Year commission, since I had ideas I wanted to work on with regards to the interaction of specific instruments and piano. The instrumentation is Flute, Clarinet, Horn, Violin, Viola, Cello and Piano, and the discovery of various timbres and juxtaposition of articulation was exciting. The sonorities that became possible through exploration of voicing and the refinement of textures was inspiring. Collaborating with those musicians throughout the process was pure joy.

I encountered your compositions through your piano solos, most notably VLA, a piece you wrote about the Very Large Array in New Mexico. It—like most of your previous piano solos—is fiercely difficult, startling, bracing, and uncompromising. Tell me about the ways you've blended your interests in things such as astrophysics with your compositions.

I will speak to the aspects of the creative ideas that have emerged from observation and interest in the natural world and scientific study. For instance, the recorded vibrations and visual solar flares of the sun, used in the opening of the augmented reality work “Song of the Stars,” used with permission from the NASA Archives, served as the foundation, the bottom of the sound, in the opening passage. The vibrations inspired a sensory response in the listeners as their phones vibrated. The vibrations began as each audience member used their phone to read the QR code on the program, thus causing the “piece” to begin. The collective sound that arose from the buzzing of the entire audienceʼs vibrating phones made the music. This was a very different compositional experience than Iʼve had previously. I created this work in collaboration with Raphael Raphael, professor of Trans-Media Arts at the University of Hawaii, for Cascadia Composersʼ Caldera Concert.

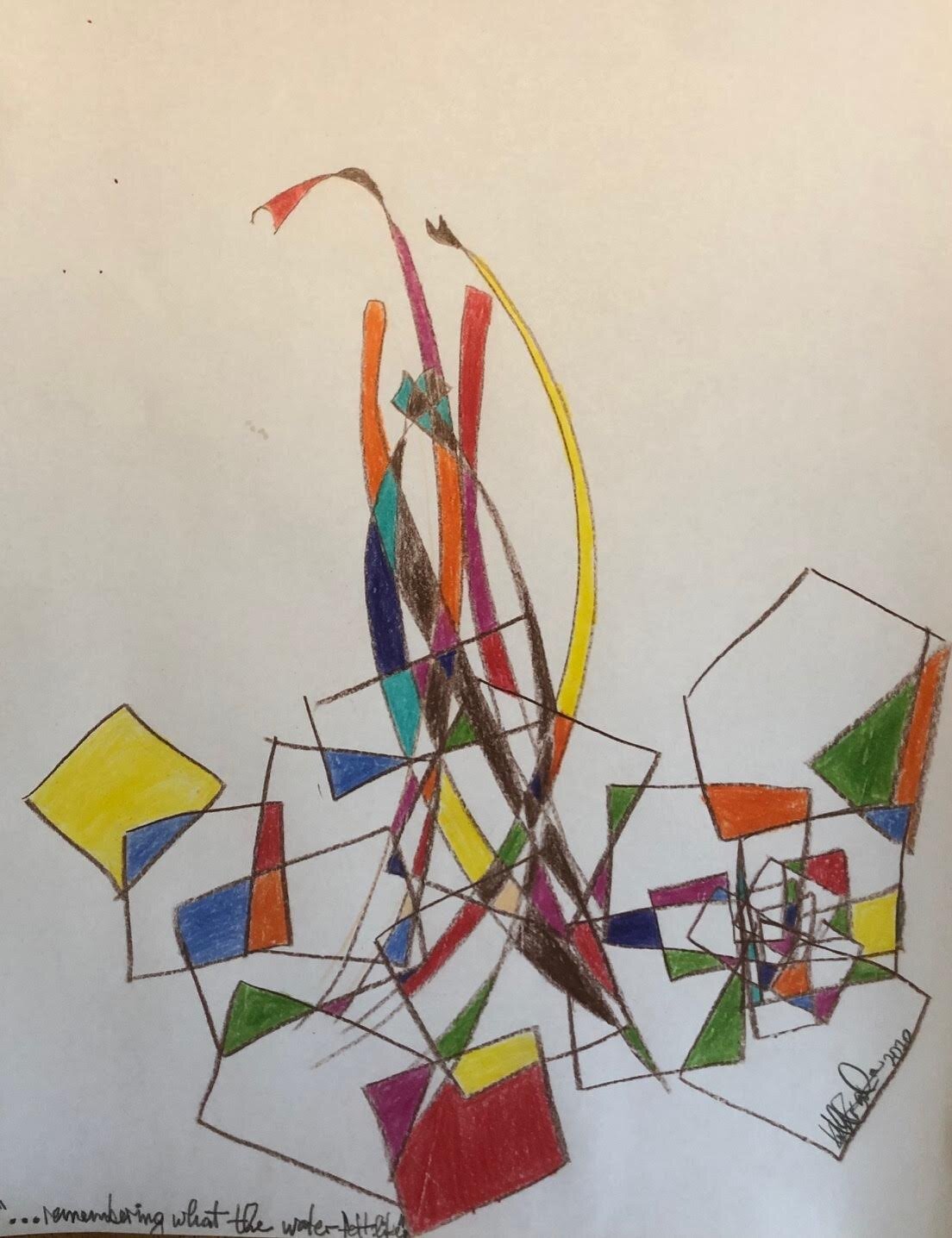

There were no actual data points that served the creative process in the composition of VLA-Very Large Array. I sketched and studied specifics about the size of the massive telescopic radio dishes, potential for projection and reception of radio waves, storage of data collected and various configurations of the dishes to reach certain depths of outer space in order to create representation in sound and physical movement. Due to parameters such as time and space (no pun intended) I settled for solo piano. I created a piece of visual art that represented my vision of the sound as it emerged from and converged on a central point. Then I composed lines that represented the outward projection of radio waves or rays that ultimately ended up looking like a spider or constellation of stars in tones on a staff. I wanted the visual image to match the sound in every way possible. From that point I created a number of transformations of those shapes of sound, each iteration called a Wave. The general form of the piece could be loosely described as continuous variation or thematic variation. Each wave had its own dynamic contours and expression that comprised its contrapuntal, rhythmic and harmonic language.

Your most recent piano solos include 18 Variations and a Coda on the Theme Frère Jacques, composed in 2019, and your most recent collection, 27 Pandemic Preludes, composed in 2020, which will be premiered on March 14. Both collections are much more accessible than your previous works. Why did you choose to write them?

I believe that music must have relevance to time and place. There are many ways this can be achieved, such as through extra-musical or literary connections, homage, dedication, style or historical trend. My primary goal is to create music that forges a connection between the present and the past, the seen and the unseen, in order to provide continuity and context. That said, it is not uncommon for my compositional language to veil common aspects of harmony.

In both of these sets of pieces, I put elements of my musical and pianistic style into perspective by presenting technical challenges in a more accessible harmonic and rhythmic language. I would not say these are pedagogical pieces, per se, but part of my goal with the Pandemic Preludes was to compose works that introduce the greater demands in my own more advanced works as well as those of other composers. Working with basic chord structures such as triads, and simple formal structures, I gesture toward complexity, dissonance and harmonic/textural layering while maintaining accessibility throughout.

Tell me more about 27 Pandemic Preludes. What images, concepts or emotions did you draw on to create them?

The pieces in the set of 27 Pandemic Preludes emerged largely as introspective, personal responses to the psychological toll brought about by the threat of the virus. Like so many composers, literary figures, visual artists and others have shown through their work, large-scale, dramatic expressions have, at their core, simple ideas. The virus acts like the nucleus of the composition. The lockdowns that began taking place worldwide were an opportunity to stop and reflect, often through these vignettes, all of which have at their core the potential to inspire a larger work. Otherwise, nature, the health of family and friends became the most important daily meditation. From the early days of the pandemic, I chose to release short recordings, as many others did as well, from my home studio, in order to share some insights into who we are, what makes us feel whole as artists. And I needed to do this since my ability to share my art through live performance was brought to a standstill almost immediately.

The pandemic has upended all of our lives. How do you feel it has affected your career and your plans for the future?

With regard to my performing career, when my live performance season was cancelled, I sought other ways to connect. We are so fortunate to have the online platform for presentation of our work. I have had a piece broadcasted on an online playlist for a NYC classical station affiliate show, was featured alongside 100+ pianists across the globe in a feature celebration of the composer Eric Satie, Satie Pandemie-Teatro Miela in Trieste, participated in a weekly radio show called Quarantine Radio where I played mixed programs of works like from Beethoven to Monk. New horizons, new challenges.

It took time to adjust but within a couple of weeks I also had my teaching studio online for lessons, and Iʼve auditioned a number of students into my studio since then, entirely online. It is different, but it is connection.

My plans for the future are to move ahead as always, perform, publish my compositions, collaborate with fellow artists, lecture and teach my students. I believe we all can learn from this experience and return to in-person life wisely. Until then, I will continue listening to the releases and concerts of my brilliant colleagues and friends who embody the hope and optimism that we all need in order to support each other and make it through this pandemic.

When I read through both 18 Variations and a Coda on the Theme Frère Jacques, and 27 Pandemic Preludes, I found them to be beautifully-crafted jewel-box miniatures that explored a wide range of compositional style and level of difficulty. Tell me about how these pieces work together to form such seamless collections.

Thank you for your kind words. The process of organizing the pieces as a set was an arduous task. As with so many volumes of preludes and etudes, they simply were not composed in order. Once I amassed a number of pieces, of course thinking about how they would work together the whole time, I stopped composing and began practicing them as I contemplated their place in the set. The variations could have continued to grow both in numbers and difficulty. So many possibilities and interesting sounds, textures and playing techniques flooded my imagination. I had to stop or it would have ended up a much longer and more difficult piece than

I felt it should be. There are few variation sets like this that are functional, medium-length concert pieces. I set out to write a piece that would be a gateway to the virtuosity found in most concert repertoire. The theme itself helped me to make this decision. So, perhaps Iʼll decide to write a couple more volumes on this theme, realize those virtuosic concepts, and consider it Frère Jacquesʼ journey from childhood to adulthood. This would be the early-adolescent volume.

You are virtually premiering 27 Pandemic Preludes on March 14, 2021, at 1:59 pm PST. How may we attend?

You can attend by subscribing to my YouTube channel: Alexander J. Schwarzkopf.

Will you be selling sheet music for these collections? If so, how may we purchase them?

I will be selling copies of both scores. These and others of my works will be available through my webpage: www.ajsmusic.org.

Alexander J. Schwarzkopf was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Alexander is regularly featured as pianist and composer at festivals and concert series such as Makrokosmos Project Festival in Portland, Oregon, Pianoforte Series at the Asheville Art Museum and Klavierfestival-Lindlar, where he has been invited for concerts and lectures. Alexander has performed cutting-edge new music by composers from the USA and abroad as well as his own works at the Oregon Bach Festival abd John Donald Robb Composers Symposiums, Cascadia Composers (NACUSA) and the Schultz Seminar at Stanford.

Alexander has given masterclasses throughout the United States, at UFRGS Conservatory in Porto Alegre, Brazil and at DTKV and Klavierfestival-Lindlar in Germany. Alexander has been a jury member for MTNA local and regional piano and composition competitions and has given lectures on his current research “Visualization in Music: Translating the Contours of Melodic Lines into Physical Movements” for Oregon Music Teachers Association Eugene and Portland chapters.

Among other awards, Alexander was a finalist at the Silvio Bengali International Piano Competition in Pianello, Italy. Known for his diverse repertoire, Alexander has been featured in performances of a wide array of works such as the Goldberg Variations by J. S. Bach, the Sonatas and Interludes by John Cage or the Makrokosmos by George Crumb. As a composer, Alexander has received commissions from organizations such as the Oregon Music Teachers Association, Bill Evans Dance and the Drama Department at the University of New Mexico. In 2017, Alexander received a commission for the award Composer of the Year for OMTA to compose a piano concerto, titled “PSi.” A finalist for the MTNA Distinguished Composer of the Year, the concerto is now in the catalogue of the national archives. Alexander has been Visiting Artist Piano Faculty at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and faculty at the Klavierfestival-Lindlar and DeutcherTonKünstlerVerein "Musik Aktiv" festivals in Germany. Alexander’s incisive recording of Falko Steinbach’s “Figures: 17 Choreographic Etudes” on the Centaur Records label can be found on Amazon, iTunes and other major catalogues internationally. Alexander holds the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance from the University of Oregon, and currently lives and conducts his private teaching studio in Eugene, Oregon.

For more information on Alexander, please visit www.ajsmusic.org.