Union Square: an interview with composer and pianist Jakub Polaczyk

It’s difficult to state just how revered Frédéric Chopin is in Poland. Warsaw alone boasts statues, a Chopin museum, notes in sidewalks, and 15 musical benches (which play Chopin’s music) scattered around the city. He’s simply everywhere, and his musical lineage is part of every Polish composer’s work.

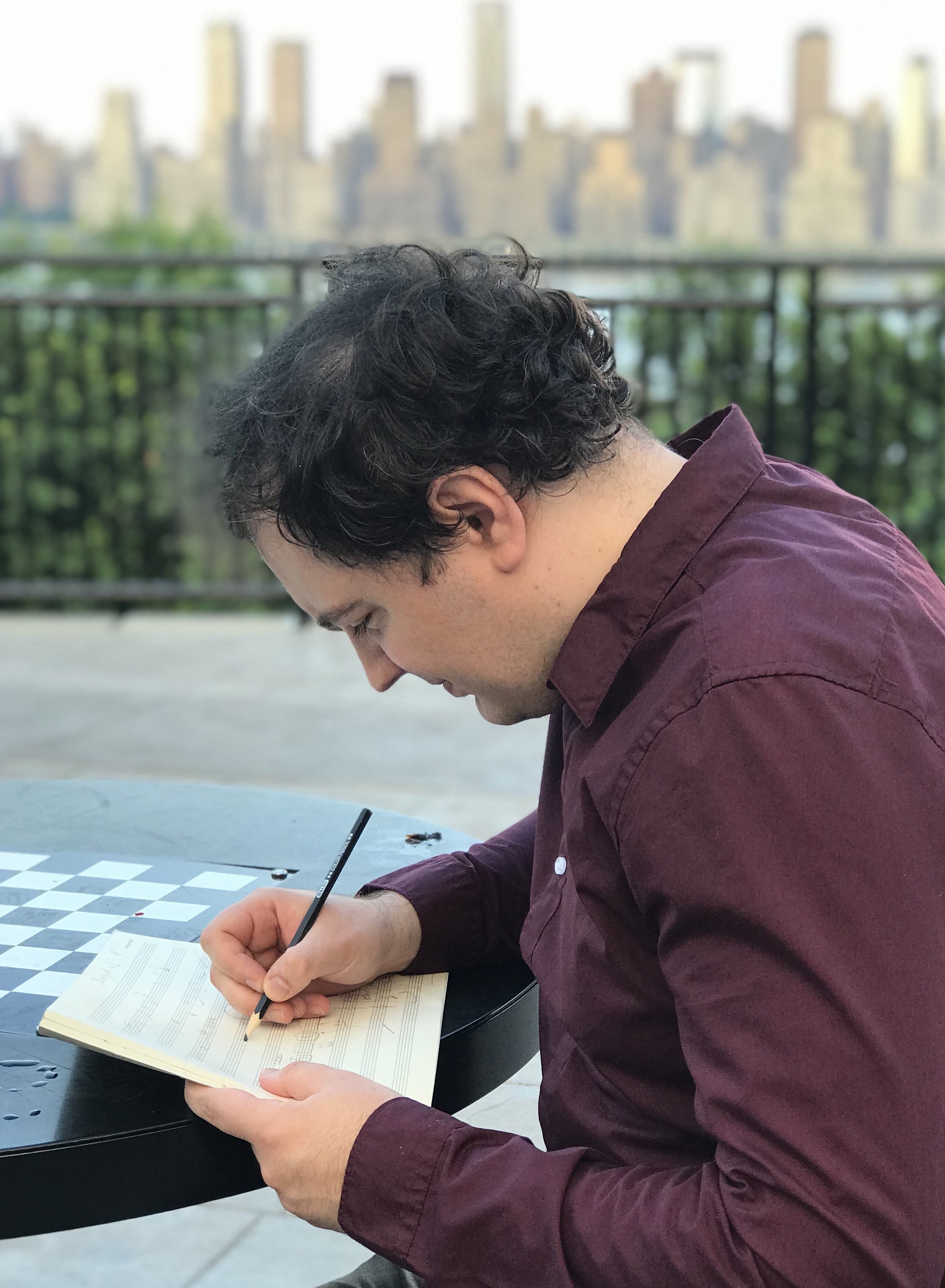

Pianist and composer Jakub Polaczyk is no exception. Along with Szymanowski, Lutoslawski, Gorecki, and Penderecki, Chopin is part of his musical DNA. On this recording, Polaczyk pays homage to one of Chopin’s most famous compositional forms—the mazurka. “Mazurka-Fantasy,” a solo piano piece played by Polaczyk, bridges the past and the present with his use of a traditional form and modern sounds. The result is music that sounds both familiar and new—contemporary with a foundation in the past. “Mazurka-Fantasy” is just one track on Polaczyk’s first autobiographical album entitled Union Square—the title chosen because Polaczyk likes to play chess with people in this New York City park where many cultures meet, interact and unite.

In his music, Polaczyk brings together the cultures of Poland and the United States, his passion for chess and modern art, and his abiding belief in the spiritual aspect of music. He has won multiple awards, including the American Prize in Composition (2020), SIMC International Compositional Competition for Harpsichord in Milan (2019), and the Iron Composer First Prize in Cleveland, Ohio (2013). Polaczyk’s works have been performed at composer conferences and music festivals in 23 states and have been premiered at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center. Additionally, his works have been performed in most European countries. It is an honor to feature him and his music on No Dead Guys

At what age did you begin music lessons, and when did you first begin composing?

I think I was 8 years old. I always loved music, but I got fascinated by it when I heard the first cassette recordings on the professional audio system that my dad bought in Germany. That was also around the time when my mom recorded a movie about John Lennon called Imagine, and I discovered the recordings of Chopin by Adam Harasiewicz. We lived in Stary Sącz (80 miles south of Krakow). I started learning acoustic guitar because it was easy and cheaper than piano. After getting a piano from my dad’s family, I started improvising more and more—but to be honest, I didn’t notate anything. I was attending a public music school. I notated my first composition when I was 18.

When did you move from Poland, your birth country, to the US, and why did you choose to do so?

I moved to Pittsburgh after graduating from the Music Academy in Krakow (now called Penderecki Academy) and I got a scholarship to study with the Iranian-American composer Reza Vali at Carnegie Mellon University. I heard about this place from my friend, the conductor Jan Pellant. He encouraged me to come to the United States to experience different cultures. I wanted to expand my musical perspective, so I gave it a try—I also liked the fact that Andy Warhol went to Carnegie Mellon! As you can see, I was very excited and happy to move to Pittsburgh to get my Artist Diploma. I got to know many artists, including visual artists, and I had a chance to visit the grave of Andy Warhol. In addition to that, I had a chance to perform contemporary music as a pianist in the Carnegie Contemporary Ensemble. We even made a recording for Naxos of the music of Leonardo Balada, a Spanish-American composer and Carnegie Mellon professor. I didn’t plan to stay in America, but my plans changed after I met my wife and we moved to New York.

It has been said that your music is “thoroughly informed by rituals,” and that some of your works “act as gateways to meditative spaces.” Can you tell me more about this?

Oh really? I was not aware of that. I am glad that people can hear it that way. That’s probably right. However, I would like to say that I always leave the interpretation of my music to the listener. There is not one correct way to hear my music. Music doesn’t need to tell a particular story—it can speak for itself in abstraction. For me, the spiritual aspect of music is especially important. It is more important than the compositional techniques and practices that we learn in the academy. I prefer to let the spirit of sound and color guide my compositional process. You mentioned meditative practices—I am glad that people can hear that aspect of my music. My music can be meditative, but there are also kinetic episodes which act as antipodes to the quiet music. You also mentioned rituals. They are important messages of expression and culture. They use gestures, words, specific objects, and actions. Those things often happen in my music. I can’t imagine music without the imaginative spiritual aspect of rituals. As a child I liked to watch processions at family gatherings—I participated in few as a child, but I always preferred to be an observer. I am still fascinated by many artistic rituals. The East Asian approach to time and color is fascinating. There is an extended sense of time which breathes. As a Pole, I do not try to imitate the sound of East Asian music, but like the French composer Messiaen, with his idiosyncratic use of Ragas, I learned how to make my music breathe by incorporating an East Asian sense of time. I also draw inspiration from Gregorian Chant. Both musical worlds serve as the foundation on which I build musical form.

The one time I was in Poland I was struck by central Chopin and Paderewski were to the culture. How have these composers (and others like them) influenced you and other modern Polish composers?

That’s right! I would also add one more name: Karol Szymanowski. I think Chopin did a lot as our grandfather. There is no doubt about his heritage in Poland. After him, Szymanowski, Lutoslawski, Gorecki, and Penderecki. They always mentioned Chopin as an important, inspiring composer. Chopin was a colorist—he had many dark and dramatic colors. He was also very experimental. He used many complex rhythms, irregular ornamentations, and unconventional harmonies for his time. The harmonies in the last movement of his Piano Sonata No. 2 in B♭ minor and the Étude Op. 10, No. 6, in E♭ minor are very forward looking. Paderewski was less experimental, but he was an important political figure and a fantastic pianist. Paderewski is considered more as the grandfather for pianists than for composers. Szymanowski took Chopin’s mazurkas and built on that form, taking them into new dimensions. He also composed many significant orchestral and chamber works. He wrote a lot of vocal music in Polish, including many songs and an opera. Most Polish composers might say that he is just as important as Chopin, but Szymanowski considered Chopin the most important Polish composer (even though Chopin wrote almost exclusively for the piano). Many contemporary composers in Poland are very experimental. While their music may sound nothing like Chopin, his spirit imbues them, nonetheless. In Poland, Chopin and Paderewski are national treasures. You can hear their music while walking on Nowy Świat Street in Warsaw.

Did communist rule affect what Polish composers could and could not write? If so, how?

I think it was a difficult time. Composers had to make sacrifices, but they found different ways to express themselves. Some, like Panufnik, even wrote songs for popular consumption. The communist party tried to control the way music was written. Many artists were able to subvert the party’s oppressive mandates by concealing the real meaning of their music. The lack of freedom forced composers to be indirect and find creative solutions to express themselves. In the 1960’s Poland was one of the leading centers for avant-garde music in Europe. Their sonorities were incredibly new. There is no doubt that Lutoslawski’s Cello Concerto and Penderecki’s Passion were dealing with this struggle for freedom with their use of controlled chaos. Serocki, another experimental composer, proclaimed freedom with his Swinging Music, a loosely constructed piece with vague, textual instructions for musical gestures and a swinging rhythm. With the use of extended techniques, composers found the freedom they did not have in the communist regime. Unfortunately, the communists attempted to censor and ban certain works. I remember Gorecki mentioned that they banned performances of his vocal work Beatus Vir. Religious music was prohibited at that time. Kotoński and Tadeusz Baird had problems as well. Some composers, like Roman Palester, emigrated because of the lack of artistic freedom. Most composers didn’t quit, they just found a way around the system.

I find it interesting that you are a concert pianist yet most of your compositions were written for other instruments, usually ensembles. Why do you think this is so?

Well, the piano is considered the king of the instruments. It has a huge range and many possibilities, but millions of composers have used it before. We should not forget that fact when we write for it. It is really difficult to write for solo piano. I love it, but I also like to blend it in with other instruments and voices in my music. That’s also why I like to play as an accompanist. I like expanding the sound of piano; extended techniques appear in my music. (Well that’s nothing new—piano has been expanded a lot in last century!) I continue to find new sonorities on the piano. For me, the piano is like a diary or a personal item. During the pandemic, I wrote 40 diary pieces for the left hand. As much as I like the piano, it has limitations. Some of my favorite music, music that is refreshing to my inner world, is written for ensemble and orchestra.

Of all your past award-winning compositions, I’m most interested in“Whistling” for which you won the title of Iron Composer in 2013. What is Iron Composer, and what parameters were you given when you composed this piece?

It was fun to use whistling. Ten years ago, I was asked to use whistling as a secret ingredient at the final competition in Cleveland. I had six hours to write a piece for brass trio. I had one rehearsal (that was the first time I conducted my music) and the concert was broadcast live on the radio in Cleveland. I was writing so fast that I even didn’t know when I had finished the piece. It was called “Finding You.” I wanted to use whistling inside the brass instruments, so at the end it appears in the public at the end of the piece. moves away to the public as the sonic field. The piece won the Iron Composer in 2013. I enjoyed using unusual non-musical elements in my piece. Often my pieces will have one or more unusual non-musical elements anyway, so it was idiosyncratic to use whistling. It was a memorable event.

I’m enchanted by “Mazurka-Fantasy,” your piece for solo piano featured on Union Square. In it you successfully brought past and present styles together. Tell me about this piece. What inspired it and how difficult was it to blend old forms with new sounds?

The piece has shadows of Szymanowski, Chopin, Maciejewski but it uses non-classical harmonies with a full range of sounds. I wanted to go forward with mazurka and expand it a bit into my colors and narration. I just let my imagination run free without worrying about how hard it would be to play. Of course, there are some mazurka rhythms, scratches of melodies, but it is like surrealistic painting—both clear and distorted musical images intermingle. In my music you can find those two contrasting worlds. Not only Polish composers wrote mazurkas: Debussy, Ravel, Lecuona, Scriabin and many, many others played with the form. I wrote it because I gave some lectures about mazurkas at the school where I teach, the New York Conservatory of Music. Professor Jerzy Stryjniak, a concert pianist, school director, and president of the conservatory, inspired me to write a mazurka again as a contemporary composer. I thought, ‘Okay, why not have a bit of fun?’ So I wrote my little mazurka and called it a ‘fantasy.’ I premiered it at Steinway Hall in New York City at the anniversary concert of the New York Conservatory of Music. I haven’t written many pieces like that, so it was a rare event.

What are some of the primary differences that you see between the way Polish and American audience receive classical music?

I think there are some. The audience is different. I have already noticed that. It has to do with education and a certain way of listening—probably because of the perception of music. In Poland music can be more detail oriented. In America, the overall impression is more important. Poland is more analytical and historical. It also varies by groups of people within each country. Particular groups listen differently. In America, the attention span is shorter. Musical colors are different. Melodies are different. In Europe, melody might not be as important. European composers’ approach to melody is more complex, like the legendary piece by Ligeti “Melodien”. In America, listening is more straightforward. But in visual art we shouldn’t forget that the abstract expressionist movement was here.

In addition to your careers as a pianist and composer, you are also a radio broadcaster. Would you be willing to tell me more about this?

Well, that’s right. Since 2020 I have been doing a program called “Coffee after Bach”. The intro music is from the “Coffee Aria” by Bach. It is in Polish. I present pieces composed after Bach or occasionally from the Baroque Era, but I mostly play a lot of new music. I presented music from the Chopin Competition, Wieniawski in Poland, and new albums from the United States and Poland. I also present biographies about composers such as Philip Glass, Witold Lutoslawski, Krzysztof Penderecki, Maurice Ravel, Alexander Scriabin, Cesar Franck, and pianists like Maurizio Pollini, Kristian Zimerman, Radu Lupu, Wanda Landowska and Glenn Gould. The program has headquarters in Chicago, but it can be heard in New York City and online as a podcast. It’s the largest Polish speaking radio station in America.

This is like my hobby—sharing music with other Polish people in America and around the world through the internet. I really like to share different music with my listeners and get weekly feedback after Sunday afternoon programs.

Tell me about the International Chopin and Friends Festival for which you are Artistic Director. What is it, what kinds of performances does it present, and how did you come to be involved with it?

The International Chopin and Friends Festival connects artists from different genres and countries in New York City. The idea is to pay tribute to Chopin. We have concerts in the Polish Consulate, Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Polish Slavic Center. There is also a New Vision Composition Competition for different groups. The founder of the festival, Marian Zak, got me involved. I composed Mass and after that I started to collaborate more closely with the festival. In 2018, I became the Director of New Music. Since 2020, I have been both the Artistic and Executive Director. Each year has a different theme. Last year was the 24th Festival, titled “Multicultural Train.” We paid tribute to Messiaen, Kilar, and Cage who had their anniversaries in 2022. It is an interdisciplinary festival; we also present artworks, videos, and poetry.

What current and future projects are you most excited about?

Currently, I am thinking about a few concerts to celebrate my 40th birthday and the release of my album. In February, there were performances of my music in a concert in Seattle and a duet in Brooklyn. I am finishing a new piece for two accordions inspired by Andy Warhol and a piece for clarinet and piano. I am looking forward to a concert for my quartet in memory of Messiaen in Göorlitz next year in 2024, where Messiaen premiered his quartet with an ensemble of prisoners.

On top of that it is hard to say what I am dreaming about—definitely a large-scale work. At the moment, I get many e-mails (questions about writing new chamber works, especially in my country). I love chamber music, but I also love orchestras. I have not had many opportunities to work with orchestras. There are some pieces that I would love to finish. There are still many drafts of works that I would like to return to. I am dreaming about something bigger like an opera. But life and music don’t always go as planned. It usually goes in its own direction. Well, I try to follow where life leads and compose in the meantime. I don’t know where life and music will lead me.

What advice can you offer to young pianist-composers who seek to create a career in both disciplines?

The two disciplines are so connected—it is hard to draw a line. Both help each other. Teaching will help you grow. You learn through teaching others and solving their problems. Compose music for your students like Bartók and Bach. Your students will know you better from the pieces you write for them, and you will also gain a new audience. Perform a lot of colleagues’ music as well as your own—it will help you gain exposure. Both practices will help you grow. Play the music as you write it, in order to get a better understanding of it. It is difficult to practice and compose but you can find a balance. Finding a balance is very important, so you need to arrange your daily schedule in a practical way. I don’t think the idea of playing for two weeks and composing for two weeks would work (as composers-conductors like Mahler would do). I recommend doing both regularly. I think it is valuable for pianists to try to compose without the instrument—you often find novel solutions.

It was my pleasure talking to you. Thank you for the interview.!

Jakub Polaczyk was born in Krakow, Poland, in 1983. He is a composer, pianist, and pedagogue. He graduated from the Penderecki Music Academy, Jagiellonian University and Carnegie Mellon University. He currently resides in New York City and is an advocate for contemporary music.

As the director of the International Chopin and Friends Festival, Polaczyk has launched a new music competition. As a radio broadcaster, he presents contemporary and classical music side by side to audiences in New York City and Chicago. As a member of the faculty at the New York Conservatory of Music, he teaches composition, music theory and piano performance.

Polaczyk’s works have won numerous top awards and recognitions, including a recent commission by Composers Guild of New Jersey (2022), American Prize in Composition (2020), SIMC International Compositional Competition for Harpsichord in Milan (2019), and the Iron Composer First Prize in Cleveland, Ohio (2013). His compositions have been performed around the world. In the United States, Polaczyk’s works have been performed at composer conferences and music festivals in 23 states and have been premiered at the Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center. Additionally, his works have been performed in most European countries.

A few of the ensembles that performed his music include: Avanti, Slee Sinfonietta, NeoQuartet, Argus Quartet, Cracow Duo, NED, Polanski Duo, Blow Up Percussion, Cracow Golden Woodwind Quintet, Four Corners, Bulgaria National Orchestra, Hanoi Philharmonics National Orchestra, Brazil National Orchestra, Janacek Symphony Orchestra, Coro Volante, and the Carnegie Contemporary Ensemble. Jakub Polaczyk is a Steinway & Sons partner and his music is published by Donemus, PWM and Babel scores.

As a pianist collaborated with: Christine Walevska, Pein-Wen, Nadia Rodriguez, Kofi Hayford, Justyna Giermola, Sarah Lucero, Beata Halska, Roberto Vasquez, Marta Płomińska, Ivan Ivanov, Wioletta Strączek, Piotr Lato, Wojtek Komsta, Anna Wilk, Agnieszka Świgut, Renata Guzik and many others singers, instrumentalists and ballet companies in NYC metropolitan area and National Opera of Krakow.

For more details, please visit Jakub Polaczk.