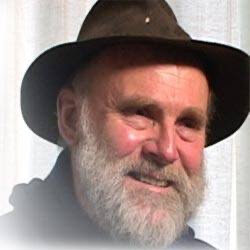

Dialogue With "Vladimir" (aka composer Dave Deason)

Composer Dave Deason has been a friend of mine for 17 years. I've recorded his music, performed it in concert, and have been an enthusiastic fan of his non-piano works. We've shared teaching stories, humorous videos, gossip, and a lack of tolerance for pomposity in any and all forms. Over the years, he started signing his emails "Vladimir", to which I responded by signing mine, "Krupskaya". When "Vladimir" agreed to be interviewed for No Dead Guys, he chose to alter it into a sort of Socratic dialogue between our nom de plumes and then "double-dog dared me" to keep it in that format. It was a dare I couldn't ignore.

Dave's informality belies his achievements. His music has been performed and recorded by artists such as Wynton Marsalis, Ramon Ricker, Chien-Kwan Lin, Dave Demsey, George Gabor, Steve Mauk, Jerry Willard, Don Butterfield, Jason Byrnes (to name a few) and heard in venues as auspicious as Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, the Juilliard School, Eastman, and many others. I'm honored to call him my friend and am thrilled that he agreed to be interviewed. (And, in case you're wondering, neither of us is Russian).

Krupskaya: You’ve composed in all genres of music, including classical chamber ensembles, concert band scores, piano music, jazz pieces, vocal works, and film scores. What has drawn you to writing for so many different instruments and groups, and what has been the most rewarding for you?

Vladimir: I first started playing clarinet in the fifth grade, later added the alto sax, and even later, the flute. I was in the marching and concert bands through graduate school. So, I have always been around a lot of wind instruments, especially in high school and college bands, some of them, by the way, having the best looking girls in the woodwind sections. As I could play several instruments, it gave me the chance to sit closer to some of these girls, for all the good that it didn’t do. I was a high school junior when a small group needed a piano player for local Jazz gigs. I began working hard to become a reasonable player. I joined the group which finally became a Jazz quintet. We played at many clubs and hotels on the east coast of central Florida.

As a student, I listened to all types of recordings including string ensembles, wind ensembles, concertos, symphonies, you name it. In those days I was hungry to know music. Besides, in college, I did not have enough money to go on dates, so I kept going to the music library to listen to pieces, most often with scores in hand. Eventually, I found that I wanted to try my hand at writing for these various groups that I heard, so I did. The ensembles that I felt least comfortable with were string ensembles, as I never learned to play strings, although I used to check out a double bass to drag into a practice room and teach myself jazz bass. In college during rehearsals, I often asked the conductor if I could sit next to string players in the orchestra as a non-player, just to get a “feel” for the internal moving lines of the music. Occasionally, I would ask players how they handled difficult spots, so I could get some feedback before writing a composition for them. Each ensemble posed different challenges, but I relished and still relish the challenges in writing for them. Besides, I enjoy working with different people and to learn their unique views about music and performance styles.

Possibly the most rewarding association for me is with sax ensembles, from small duos to large groups. Sax players are some of most enjoyable people to have a blast with.

The bottom line is that composers must work with and listen to what performers tell them.

Krupskaya: By your own description, your own compositional style features a distinct jazz influence – one that contrasts rhythmic, high energy movement with lyrical ballad. You came of age as a composer in an era of avant-garde classical music. What drew you away from that language and into jazz?

Vladimir: I was trained in the classical tradition in my youth. When I became a college student and really discovered contemporary music, I, too, became enamored with avant-gardism in composition. During my undergraduate years, I wrote pieces somewhat modeled after my heroes at the time, Schoenberg, Beg, and especially Webern. I also delved into Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio, Xenakis, Maderna, Luigi Nono, and others, almost exclusively Europeans. We felt that Samuel Barber was a sell out to commercialism. It was years later that I realized that a host of Americans, including Barber, are among the most significant composers of the 20th century. It was also later that I became acquainted with Elliott Carter, Charles Wuorinen, and others of a decidedly more avant-garde bent among Americans. One would have to look very hard to find anything about Carter in Florida in the late 60s. But I eventually got weary of being among what we fashioned a more ‘enlightened’ contingent of the musical public. Sometimes players told me that my avant-garde pieces “reeked”, which was not intended to be a compliment. Eventually, I got tired of explaining to people why I was writing in a style that few found enjoyable. I found myself becoming an apologist for this style.

The jazz influence in my writing came along later. As I mentioned earlier, I played jazz way back in high school. I also played in the stage bands in college. But jazz did not appear in my writing until years later, for some reason. I now regret that I did not employ my love of jazz earlier, as I could have avoided writing many uninspired pieces. My main influences were Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans in my piano writing, J.J. Johnson and Miles Davis in my brass writing, and certainly Henry Mancini and Gil Evans in my melodic attempts. There are many others, too numerous to mention. I got to know Wynton Marsalis when he was a student at Juilliard. He premiered a piece of mine called Doubletake for Alto Sax and Trumpet, a piece that still sells today.

I don’t think my stuff would be considered ‘real’ jazz for a number of reasons. I still love classical styles, with its emphasis on contrapuntal lines, strong bass lines, etc. If anything, my pieces might be considered as a kind of post ‘Third Stream’, but less avant-garde than the jazz pieces by Gunther Schuller or Hall Overton, for example.

Krupskaya: When you approached me to record the music for your first CD, Oregon Impressions, I fell in love with how beautifully-crafted and lyrical the pieces are. You somehow succeed in mixing sophistication with down-home melodies, and out of the mix you get something that’s both utterly unique and completely approachable. How do you do this?

Vladimir: Ah, the HOW question! Answering that is almost as difficult as answering the WHY question! This is the same question I ask myself when I read about Einstein’s Special and General Relativity. How the Hell did he do this? Or, when I see photos and videos of the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, I ask once again how in the world did they conceive and build this marvel? When I study one of my favorite pieces of music, the B minor Mass by JS Bach, once again I marvel at his ability to write this. Yes, we can study the rhetorical devices that Bach used in his construction of this masterpiece, so we can conjecture about how Bach did this. But, on the deeper human level, how did he REALLY do this? Of course, many very smart people have tried and continue to study how exceptional humans are able to do extraordinary things. Judging from the plethora of Phd dissertations in the psychological and sociological arts, the quest for HOW someone does something may never stop being asked. For me, the answer to the question of HOW is similar to the difficulty of defining what “inspiration” is. Whatever the answer is might just be too elusive. Ultimately, the question is probably unanswerable.

However, my original impetus for Oregon Impressions grew out of my friendship with the owners of Roads End Films, an indie film company in Newberg, Oregon. Living in Oregon with its spectacular mountains, gorgeous scenery, and, of course, the famous Oregon coast, how would it be possible NOT to be inspired by all this? Anyway, after writing the pieces, I then needed to find a fine player to record them. At that time, I did not know any pianists in the Portland area.Then someone suggested I contact this Rhonda person who was a terrific pianist, so I proposed the project to her. She accepted. We recorded the pieces at the Big Red studio under Billy Oskay in Corbett, Oregon.

Afterwards, Road’s End Films took some of the pieces and created a beautiful short movie called Oregon Impressions – A Visual Journey. As for how I did this, I have no idea, other than saying that I just allowed myself to be inspired by the uniqueness and majesty of Oregon.

Krupskaya: In 2008, you composed the score to the indie film, From Kilimanjaro With Love, winning an award for your efforts. How were you chosen for this project and had you ever written a film score before this one?

Vladimir: The aforementioned Roads End Films had already filmed the movie when they contacted me about doing a score for it. Initially, I was reticent about doing it, since I had never done a film before. However, I was provided with a small video player which I placed beside my computer and keyboard. I used this player to divide the film into sections, where I could focus on each scene individually, hoping to be inspired enough to write something was worthwhile. I hashed through scene after scene, finally putting them back together. My object was to write musical ideas that were associated with each character, mood, and location. I combined these ideas in various ways in a kind of Wagnerian ‘leitmotif’ manner. I must add that as this was a low budget and locally produced project, so the director, the music editor, and I enjoyed a camaraderie that was free from financial pressure, ego trips, and angry outbursts that one often hears about in the movie industry. In other words, we had fun. Sometimes the music editor took music I earmarked for a certain scene and used it very effectively in other scenes. From Kilimanjaro With Love was premiered at the LA Indiefest 2008. It was at this premier that I was told that the score was nominated for best score. Of course, it did not win, but I felt good about it, partially due to the fact that my score was picked over some big guys.Truth be told, there were many times I felt that I didn’t know what the Hell I was doing!

Krupskaya: How is film scoring different than other types of composing you do, and how closely did you work with the director and the script as you were creating this score?

Vladimir: Of course, I was in contact with the director frequently as I worked on the music. As I mentioned however, the movie was already filmed when I was given the project, so all the crew had to do was to wait until I finished the score.

Writing the score was very different than composing in other genres for me because the score involved a lot of music and had to be tailored to fit the character of the movie. Of course, a live orchestra was not possible, so I used a digital orchestra.This meant that I did not have to worry about limits on what could be playable by living players. Of course, many films use the same method. We can’t all have the access to live players that John Williams enjoys.

The project was, for me, overall enjoyable. But don’t even ask how much we were all paid!

Krupskaya: Many composers find their compositional skills decline as they get older. You continue to compose for multiple groups all over the world, and your music is, in my opinion, growing richer and stronger each year. How have you succeeded in keeping your music so fresh and vital?

Vladimir: Many thanks for those kind words! Sadly, the decline of physical skills is one of the first things we all experience as we age. My first reaction to your question is that an observable decline might be more evident in performers.This is particularly true concerning the exacting skills needed by instrumentalists, dancers, or the voice in the case of singers. In this respect, the decline may be akin to similar observations noticed in the sports world. Of course, there is also the decline in mental skills to varying degrees that often accompany aging. Happily, many great performers have retained both high levels of mental and physical skills as they moved into advanced age.

Certainly composers, writers, and painters don’t really need finely tuned physical skill to the same degree as performers.So long as the brain still functions, and—above all—the ‘surge’ to create is still present, there is no reason why a composer, writer, or a painter can’t keep producing until they push up daisies. It is well known that there are plenty of examples of creative people who continued to produce great works even into advanced age. Contrarily, we can all list plenty of creative people who ended up having a short lifespan, but who, nevertheless, still had a great creative impact. So, the lifespan of an individual plays a critical role in one’s creative output. One must simply hope that one lives long enough to create a body of work.

I referred to the ‘surge’, because this is perhaps the most important attribute a creative person can have, especially as he or she may grow tired of writing or painting, etc. This is even more important as one experiences a higher level of diminishing expectations, such that youthful dreams may ultimately seem unattainable. In a word, one may not become as famous as one imagined when young, where the sky was the limit. The composer may not see as many performances as he or she hoped, the painter may still have a barn full of unsold canvasses, the performer may not sell as many recordings as he or she envisioned.

If I am getting better, then I attribute it to the ‘surge’ to create still being present. I do feel that both my understanding of how music works, and my increased understanding of myself, play an important part in my writing, as I look down that dark, forbidding tunnel of inevitable mental ossification.

Krupskaya: Which of your compositions has been your listeners’ favorites?

Vladmir: I’m not sure how to answer that question without asking the listener. If you go by, say, the number of recordings sold, or the number of you tube likes, or by the number of performances, then maybe those can give a clue as to what a peripatetic individual ‘likes’. However, I would say that the response to several of my chamber ensembles has been strong. My Gossamer Rings for soprano sax and concert band has been performed multiple times since the premier by the US Navy Band way with Dr. Steve Mauk back in ’83. My CD called From Another Time for Piano and String Orchestra received strong praise from several prominent jazz writers. Also, the response to my Wind Tunnels for trombone quartet which was recorded last year by the Szeged Trombone Ensemble in Hungary has been quite strong.

However, what I hear from people who do not know me, and who do not have a vested interest in caressing my ego, I find most useful in determining whether a piece I write has an appeal or not. Ultimately, why someone likes or dislikes something is a mystery. I still like Edsel cars…….

Krupskaya: What current or future project are you most excited about right now?

Vladimir: I recently finished a new woodwind quintet I am calling Rage Over a Lost Parking Space, an homage to you know who….Now I am hard at work on a new Trio for Flute, Cello, and Piano called The Astronomy Lesson.

I find that what I am working on at the time is the one I am most excited about. I have plenty of time later to hate it! Which reminds me that most of what I have written over the years I didn’t like. However, I’m still having a blast writing for small groups of instruments. It is a lot cheaper than playing golf.

Krupskaya: You’re a retired music professor and have decades of teaching experience. What advice would you offer to young composers just starting their careers?

Vladimir: There is plenty of room for everyone who wants to compose. There is also plenty of time for history to ferret out the majority of creative efforts that will sink into oblivion. So, assuming a talent and a hunger to learn are present, then that ‘surge’ I mentioned earlier needs to be strong, because of the inevitable disappointments that will arise during one’s career.

On a practical level, a budding composer needs to find a way to eat and pay the rent. Traditionally, a college or public gig solved that problem. However, as more trained musicians are churned out of the university or college system, competition for college jobs is much more difficult. In today’s world, a budding composer must have a PhD or DMA, hopefully in a related area, such as Theory as I did, or maybe Ethnomusicology. Composition degrees are meaningless in my opinion. Hoping to make a living as a film composer is next to impossible. However, I feel that the smartest thing for a young composer is to get certified in Music Education, thus opening a much bigger world of ways to generate an income. One thing is for sure—being a composer does not feed most of us.

Therefore, a young composer needs to have a back-up plan, such as inheriting money, or marrying someone who has a good job and, who doesn’t mind tolerating someone who spends most waking time in a room churning out scores (or books or paintings). I think it is almost impossible to have a full-time regular job, then to come home to compose at night with a fresh mind. Unfortunately, our society is generally not the friend of the creative artist. But the important thing is to keep composing and turning out a large body of work. This, I think, is critical.

I realize that this answer is not exactly what you might have expected. I hasten to add that, even in a world where there are so many obstacles to maintain a creative life, composing can be the greatest personal joy someone can experience. It is that joy that keeps me going.

About "Vladimir" (aka Dave Deason)

I am a composer, pianist, organist, woodwind player, and retired college professor. I was born in South Dakota in 1945, reared in South Carolina and Florida. If pressed, I would say that I am, at heart, a Southerner. Although classically trained, I began playing Jazz piano professionally while in high school, playing up and down the Florida coast with my Quintet, where I was the pianist and occasionally the clarinet player. I hold the B.M. and M.M. degrees from Florida State University, and the D.M.A. from the Ohio State University. My teaching background includes Lander University, Montclair University, the New School, and the Ohio State University.

Along the way, I received numerous composition and teaching awards, including numerous ASCAP awards, “Meet the Composer” grants, third prize in the American Bandmasters Association Competition (1987), the Oregon Music Teachers’ Association Composer of the Year (2000), and a National Teaching Fellow designation (1984).

I compose in all genres of music, including classical chamber ensembles, concert band scores, piano music, Jazz pieces, vocal works, and film scores. My musical language features a distinct Jazz influence, often including high-pressure very rhythmic fast movements, yet often tempered by lyrical Ballad-style slow movements.

Performers of my humble efforts include Wynton Marsalis, Ramon Ricker, Chien-Kwan Lin, Dave Demsey, George Gabor, Steve Mauk, Jerry Willard, Don Butterfield, Jason Byrnes, the late Meir Rimon, Craig Kirchhoff, the Amherst Sax Quartet, and especially the Verismo Trio, among others. My Gossamer Rings for Soprano Saxophone and Band was premiered in 1983 by the US Navy Band. It has since been performed more than a dozen times at several universities around the US.

My compositions have been heard in New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall, Town Hall, the Juilliard School, Eastman School, the Manhattan School, Indiana University, Michigan State University, the Ohio State University, and in many other universities and cities across the US, Brazil, and Israel. My Carnival was recorded by the Eastman Saxophone Project in 2012. My Trio for Flute, Soprano Saxophone, and Piano was recently recorded by the wonderful Verismo Trio of the University of Wyoming.

I produced two CDs, Oregon Impressions, and From Another Time and Other Original Ballads for Piano and String Orchestra, with myself as piano soloist, accompanied by a string orchestra. Both CDs received very positive reviews, including Jazz Police and JazzChicago.net.

My wife, Mary, and I with our Scottish Terriers recently moved to Kentucky after living 24 years in Portland, Oregon.

For more information, visit Dave Deason